Diprotodon optatum Owen, 1838a:362-363, xix

Giant wombat, ?yamuti (Tunbridge, 1988, 1991:72,89)

Taxonomy & Nomenclature

Synonyms: Dinotherium australe Owen, 1843; Diprotodon australis Owen, 1844; Diprotodon annextans McCoy, 1861; Diprotodon minor Huxley, 1862; Diprotodon longiceps McCoy, 1865; Diprotodon loderi Krefft, 1873a; Diprotodon bennetti Krefft, 1873b; Diprotodon bennettii Owen, 1877

Conservation Status

Extinct

Last record: 44ka (Johnson et al., 2016)

Diprotodon was the first Australian megafauna species to be described, based upon fossils collected by the explorer Thomas Mitchell in 1830 from the world famous Wellington Caves. It also appears to have been one of the most recent megafauna extinctions (Johnson et al. 2016), along with Zygomaturus trilobus and perhaps some of the sthenurine kangaroos.

Distribution & Habitat

Australia

Type locality: "coll. by Mitchell, 1830, in "the large cave"" (Dawson, 1985:66)

Anatomy & Morphology

A mass of 1000kg (Johnson & Prideaux, 2004:557) and then 2700kg has been given (Johnson, 2006:18). The maximum weight of males of the Giant wombat (D. optatum) have been estimated to be 2786kg (Wroe et. al. 2004), which would make it the largest known marsupial to have ever lived.

Biology & Ecology

It was a browser (Johnson, 2006:18).

Hypodigm

Holotype: BM M10796 (Dawson, 1985:66)

Other specimens:

QMF44649 ("P3")

NMV P31299 (cranium) (Sharp, 2014)

NMV P151802 (lower mandible) (Sharp, 2014)

NMV P157382 (lower mandible) (Sharp, 2014)

SAMA P10554 (Matthews et al., 2025)

SAMA P19444 (Matthews et al., 2025)

MV P201266 (Matthews et al., 2025)

MV P201267 (Matthews et al., 2025)

Media

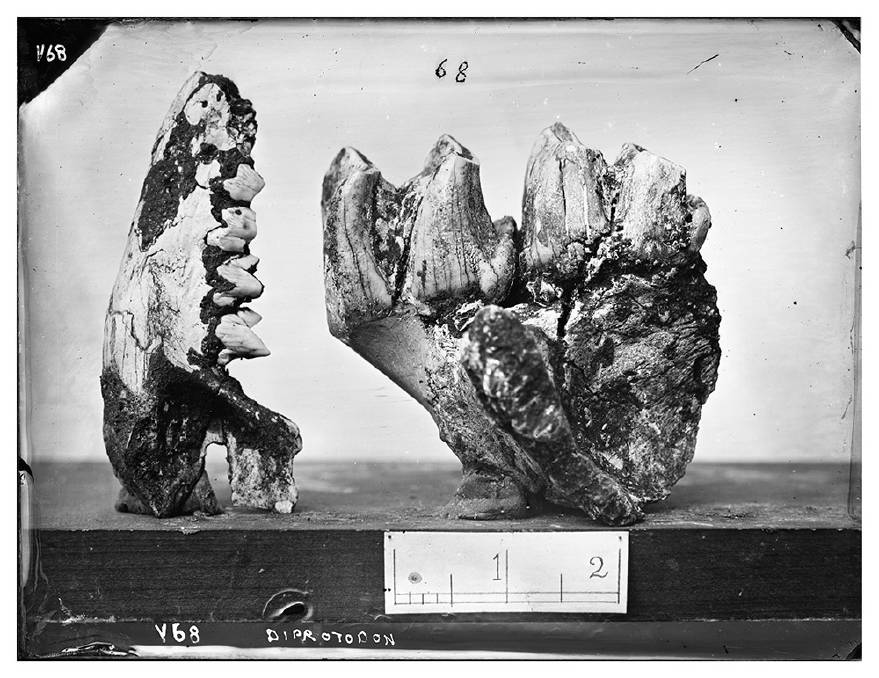

"Diprotodon teeth excavated from Wellington Caves. Australian Museum."

Source: MacLennan, Sally. (2020). At the Museum: Have you even seen a two tonne wombat? Central Western Daily, available from: https://www.centralwesterndaily.com.au/story/6837198/at-the-museum-have-you-even-seen-a-two-tonne-wombat/

Agnozoology

A traditional bunyip account is that of an encounter by mineralogist Charles Bailly with an unknown animal bellowing in the reeds up the Swan River, Western Australia, in June 1801. Although (Michell & Rickard, 1982) hypothesise that it might refer to living Diprotodon.

The explorer Hamilton Hume encountered a 'hippopotamus' in Lake Bathurst, New South Wales in 1821, which might refer to a living Giant wombat (Gilroy, 1976; Michell & Rickard, 1982). Michell & Rickard (1982) included this and another possible encounter.

References

Original scientific description:

Owen, Richard. (1838a). Letter in: Mitchell, Thomas L. Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia, with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix, and of the present colony of New South Wales. Vol. 1. London: T. & W. Boone, 343 pp. [relevant citation?]

Other references:

Ameghino, F. (1902). Le Pyrothérium n'est pas parent du Diprotodon. Anal. Mus. Nac. Buenos Aires. VIII, 223-224.

Anderson, C. (1924). The largest marsupial. The Australian Museum Magazine 2(4): 113-116.

Anderson, C. (1933). The Fossil Mammals of Australia. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 58: ix-xxv.

Anderson, C. and Fletcher, H. O. (1934). The Cuddie Springs bone bed. The Australian Museum Magazine 5(5): 152-158.

Archer, M. (1977). Origins and subfamilial relationships of Diprotodon (Diprotodontidae, Marsupialia). Mem. Qld. Mus. 18(1): 37-39.

Archer, Michael. (1984). 6.7 The Australian marsupial radiation, pp. 633-808. In: Archer, M. and Clayton, G. (eds.). Vertebrate Zoogeography and Evolution in Australasia (Animals in Space and Time). [Carlisle?] Western Australia: Hesperian Press.

Archer, M. et al. (1991). Australia's Lost World, Riversleigh, World Heritage Site. New Holland Publishers.

Archer, Michael, Arena, Derrick A. et al. (2006). Current status of species-level representation in faunas from selected fossil localities in the Riversleigh World Heritage Area, northwestern Queensland. Alcheringa, Special Issue 1: 1-17.

Basedow, H. (1914). Aboriginal rock carvings of great antiquity in South Australia. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 44: 195-211. [reports possible Diprotodon footprints]

Boogaart, W. L. (1989). Diprotodon Australis. Het grootste Australische buideldier. Cranium 6(1): 10-14.

Bourman, R. P., Prescott, J. R., Banerjee, D., Alley, N. F. and Buckman, S. (2010). Age and origin of alluvial sediments within and flanking the Mt Lofty Ranges, southern South Australia: a Late Quaternary archive of climate and environmental change. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 57(2): 175-192. [Abstract]

Brook, Barry W. and Johnson, Christopher N. (2006). Selective hunting of juveniles as a cause of the imperceptible overkill of the Australian Pleistocene megafauna. Alcheringa 30(sup1): 39-48. [Abstract]

Burness, G. P. et al. (2001). Dinosaurs, dragons and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98: 14518-14523.

Camens, Aaron Bruce and Carey, Stephen Paul. (2013). Contemporaneous Trace and Body Fossils from a Late Pleistocene Lakebed in Victoria, Australia, Allow Assessment of Bias in the Fossil Record. PLoS ONE 8(1): e52957.

Carey, Stephen P. et al. (2011). A diverse Pleistocene marsupial trackway assemblage from the Victorian Volcanic Plains, Australia. Quaternary Science Reviews 30(5): 591-610. [Abstract]

Condon, H. T. (1967). Kangaroo Island and its vertebrate land fauna. Australian Natural History 15(12): 409-412.

CRICK, G. (1900). GC Crick—Cretaceous Socks of Natal and Zululand. 339 admirable description already published by Dr. Stirling and Mr. Zietz. As pointed out by M. Dollo, 2 the reduced and opposable inner digit of the hind foot suggests that the immediate ancestors of Diprotodon were arboreal in habit. Bull. Sci. France et Belg, 33, 278-283.

Dawson, Lyndall. (1985). Marsupial fossils from Wellington Caves, New South Wales; the historic and scientific significance of the collections in the Australia Museum, Sydney. Records of the Australian Museum 37(2): 55-69.

Dawson, L. and Augee, M. L. (1997). The late Quaternary sediments and fossil cave vertebrate fauna from Cathedral Cave, Wellington Caves, New South Wales. Proc. Linn. Soc. N.S.W. 117: 51-78.

De Vis, Charles W. (1883). On remains of an extinct marsupial. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 8: 11-15.

De Vis, Charles W. (1887a). On an extinct mammal of a genus apparently new. The Brisbane Courier (August 8th) 9224(44): 6.

De Vis, Charles W. (1887b). On a supposed new species of Nototherium. Abstracts and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of NSW for December 28th, 1887. Republished 1888, Zool. Anz. 11: 122.

De Vis, Charles W. (1888). On Diprotodon minor Hux. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland 5: 38-44.

De Vis, Charles W. (1893). The Diprotodon and Its Times. The Inquirer and Commercial News, Friday, 22 December, p. 31.

Dodson, John et al. (1993). Humans and megafauna in a late Pleistocene environment from Cuddie Springs, north western New South Wales. Archaeology in Oceania 28(2): 94-99.

Dollo, L. (1900). Le pied du Diprotodon et l'origine arboricole des Marsupiaux. Bull. Scientifique de la France et de la Belgique, 275-250.

Dugan, K. G. (1980). Darwin and Diprotodon: the Wellington Caves fossils and the law of succession. In Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales (Vol. 104, No. 4, pp. 262-272). [relevant citation?]

Dun, W. S. (1894). On a vertebra from the Wellington Caves. Records of the Geological Survey of New South Wales 4(1): 22-25. [likely D. australis]

Fensham, Roderick J. and Price, Gilbert J. (2013). Ludwig Leichhardt and the significance of the extinct Australian megafauna. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture 7(2): 621-632.

Fergusson GJ, Rafter TA. 1959. New Zealand 14C age measurements IV. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 2: 208-241.

Fethney, J., Roman, D. and Wright, R. V. S. (1987). Uranium series dating of Diprotodon teeth from archaeological sites on the Liverpool plains. Proceedings of the fifth Australian conference on nuclear techniques of analysis, pp. 24-26.

Field, Judith and Dodson, J. (1999). Late Pleistocene megafauna and archaeology from Cuddie Springs, south-eastern Australia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 65: 275-301.

Fillios, M., Field, Judith and Charles, B. (2010). Investigating human and megafauna co-occurrence in Australian prehistory: Mode and causality in fossil accumulations at Cuddie Springs. Quaternary International 211(1-2): 123-143.

Flannery, Timothy F. and Gott, B. (1984). The Spring Creek locality, southwestern Victoria, a late surviving megafaunal assemblage. Australian Zoologist 21(4): 385-422.

Fletcher, H. O. (1948). Fossil hunting 'west of the Darling' and a visit to Lake Callabonna. The Australian Museum Magazine 9(9): 315-321.

Fletcher, H. O. (1954). Giant marsupial remains at Brewarrina, New South Wales. The Australian Museum Magazine 11(8): 247-251.

Fortean Times. (year?). volume 48, p. 11.[incomplete citation]

Furby, J. (1995). Megafauna Under the Microscope: Archaeology and Palaeoenvironment at Cuddie Springs. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, School of Geography, UNSW, Sydney.

Furby, J. and Jones, R. (1994). Cuddie Springs: new light on Pleistocene megafauna. Abstracts of the fourth conference on Australian vertebrate evolution, palaeontology and systematics, Adelaide, 19-21 April, 1993. Records of the South Australian Museum 1994. [Abstract]

Gerdtz, W. D. and Archbold, N. W. (2003). An early occurrence of Sarcophilus laniarius harrisii (Marsupialia, Dasyuridae) from the Early Pleistocene of Nelson Bay, Victoria. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 115: 45-54.

Gill, Edmund D. (1953). Geological evidence in western Victoria relative to the antiquity of the Australian Aborigines. Mem. Nat. Mus. Melbourne 18: 25-92, 4 pls.

Gill, Edmund Dwen. (1955). The range and extinction of Diprotodon minor. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, New Series 67(2): 225-228.

Gill, Edmund Dwen. (1963). The Australian Aborigines and the Giant Extinct Marsupials. Australian Natural History 14(8): 263-266.

Gill, Edmund Dwen. (1967). Melbourne Before History Began. Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney.

Gill, Edmund Dwen and Banks, M. R. (1956). Cainozoic history of Mowbray Swamp and other areas of north-western Tasmania. Records of the Queen Victoria Museum Launceston, N.S. 6: 1-41.

Gillespie, Richard, Fifield, L. Keith, Levchenko, Vladimir and Wells, Rod. (2008). New 14C ages on cellulose from diprotodon gut contents: explorations in oxidation chemistry and combustion. Radiocarbon 50(1): 75-81.

Gilroy, Rex. (1976). Australian monsters. Psychic Australian [1976]: pagination?.

Glauert, Ludwig. (1912a). The Mammoth Cave (Contd.). Records of the Western Australian Museum 1(2): 39-46.

Glauert, Ludwig. (1912b). Fossil marsupial remains from Balladonia in the Eucla Division. The Balladonia "Soak". Records of the Western Australian Museum 1(2): 47-65.

Glauert, L. G. (1926 "1925"). A list of Western Australian fossils. Supplement no.1. West. Aust. Geol. Surv. Bull. 88: 36-71. [Diprotodon australis]

Glauert, Ludwig. (1948). The cave fossils of the South-West. Western Australian Naturalist 1: 100-104.

Gregory, J. W. (1906). The Dead Heart of Australia. London: John Murray.

Gröcke, D. R. (1997a). Distribution of C3 and C4 plants in the late Pleistocene of South Australia recorded by isotope biogeochemistry of collagen in megafauna. Australian Journal of Botany 45: 607-617.

Gröcke, D. R. (1997b). Stable-isotope studies on the collagenic and hydroxylapatite components of fossils: Palaeoecological implications. Lethaia 30: 65-78.

Hamm, G., Mitchell, P., Arnold, L.J. et al. (2016). Cultural innovation and megafauna interaction in the early settlement of arid Australia. Nature 539: 280-283.

Hochstetter, Ferdinand von. (1859). Notizen über einige fossile Thierreste und deren Lagerstätten in Neu-Holland-Über Diprotodon australis (Owen), und Nototherium mitchelii (Owen). Sitzungsberichte der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Classe der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenchaften 35: 349-358.

Hocknull, Scott A. et al. (2020). Extinction of eastern Sahul megafauna coincides with sustained environmental deterioration. Nature Communications 11: 2250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15785-w

Hope, J. H. (1973). Mammals of the Bass Strait Islands. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 85(2): 163-196. [remains from King Island]

Hope, J. H. (1984). 1.6 The Australian Quaternary, pp. 75-81. In: Archer, M. and Clayton, G. (eds.). Vertebrate Zoogeography and Evolution in Australasia (Animals in Space and Time). [Carlisle?] Western Australia: Hesperian Press.

Horneman, Trent. (2013). Our 'Giant Wombat'. Riverine Herald, p. 1, March 27.

Howchin, W. (1891). (Abstract of Proceedings). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 14: 361.

Howchin, W. (1930). The Building of Australia and the Succession of Life with Special Reference to South Australia. Adelaide: Harrison Weir, Government Printer.

Huxley, Thomas Henry. (1862). On the premolar teeth of Diprotodon, and on a new species of that genus. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 18(1-2): 422-427. [Abstract]

Jackson, Stephen M., Travouillon, Kenny J., Beck, Robin, M. D., Archer, Michael, Hand, Suzanne J., Helgen, Kristofer M., Fitzgerald, Erich M. G. and Price, Gilbert J. (2024). An annotated checklist of Australasian fossil mammals. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 48(4): 548-746. https://doi.org/10.1080/03115518.2024.2434062

Janis, Christine M. (1987). A reevaluation of some cryptozoological animals. Cryptozoology 6: 115-118.

Johnson, Chris N. (2006). Australia's Mammal Extinctions: A 50 000 Year History. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. x + 278 pp. [p. 17, 18, 21 (drawing), p. 30-32, p. 108-111]

Johnson, Chris N. et al. (2016). What caused extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna of Sahul? Proc. Biol. Sci. 283(1824): 20152399.

Johnson, Chris N. and Prideaux, Gavin J. (2004). Extinctions of herbivorous mammals in the late Pleistocene of Australia in relation to their feeding ecology: no evidence for environmental change as cause of extinction. Australian Ecology 29: 553-557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2004.01389.x

Keast, A. et al. (1972). Evolution, Mammals and Southern Continents. New York: State University of New York Press.

Keble, R. A. (1945). The stratigraphic range and habitat of the Diprotodontidae in southern Australia. Proc. R. Soc. Vict. 57: 23-48.

Krefft, Gerard. (1873a). Natural History. Review of Professor Owen's papers on the fossil mammals of Australia. The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (August 23rd) 686(16): 238 (cols. 1-4).

Krefft, Gerard. (1873b). Natural History. Mammals of Australia and their classification. Part 1 Ornithidelphia and Didelphia. The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (November 8th) 697(16): 594-595, supp. pls. 1-2.

Krefft, Gerard. (1875). Remarks on the Working of the Molar Teeth of the Diprotodons. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 31(1-4): 317-318.

Lane, Edward A. and Richards, Aola M. (1963). The discovery, exploration and scientific investigation of the Wellington Caves, New South Wales. Helictite 2(1): 3-53, 8 pls.

Langley, Michelle C. (2020). Re-analysis of the “engraved” Diprotodon tooth from Spring Creek, Victoria, Australia. Archaeology in Oceania. DOI: 10.1002/arco.5209 [Abstract]

Leichhardt, F. W. L. (1847). Journal of an overland expedition in Australia from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, a distance of upwards of 3000 miles, during the years 1844-1845. (T. & W. Boone: London).

Leichhardt, F. W. L. (1855). Remarks on the bones brought to Sydney by Mr Turner. Further papers Relative to the discovery of gold in Australia: in continuation of papers presented February 14, 1854. (George Edward Eyre and William Spottswoode: London).

Leichhardt, F. W. L. (1867-1868). Notes on the geology of parts of New South Wales and Queensland made in 1842-3 by Ludwig Leichhardt. In Clarke, W.B. (ed), Ulrich, G.H.F. (trans) Australian Almanac. (John L. Sheriff: Sydney).

Lemoine, Rhys Taylor, Buitenwerf, Robert, Faurby, Sören and Svenning, Jens-Christian. (2025). Phylogenetic Evidence Supports the Effect of Traits on Late-Quaternary Megafauna Extinction in the Context of Human Activity. Global Ecology and Biogeography 34(7): e70078. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.70078 [Supporting Information: Data S1]

Long, John et al. (2002). Prehistoric Mammals of Australia and New Guinea, One Hundred Million Years of Evolution. Sydney: University of NSW Press.

Long, J. and Mackness, B. (1994). Studies of the late Cainozoic diprotodontid marsupials of Australia. 4. The Bacchus Marsh Diprotodons—Geology, sedimentology and taphonomy. Rec. S. Aust. Mus. 27(2): 95-110.

Longman, H. A. (1924). The zoogeography of marsupials, with notes on the origin of Australian fauna. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 8(1): 1-15.

Lydekker, Richard. (1894). Marsupials and Monotremes. London: W. H. Allen and Co.

Mackness, B.S. and Godthelp, H. (2001). The use of Diprotodon as a biostratigraphic marker of the Pleistocene. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 125: 155-156.

Mahoney, J. A. and Ride, W. D. L. (1975). Index to the genera and species of fossil Mammalia described from Australia and New Guinea between 1838 and 1968. Western Australian Museum Special Publication 6: 1-250.

Major, R. B. and Vitols, V. (1973). The geology of Vennechar and Borda 1:50000 map areas, Kangaroo Island. Mineral Resources Review, South Australia 134: 38-51.

Marcus, L. F. (1976). The Bingara Fauna: a Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from Murchison County, New South Wales, Australia. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 114: 1-145.

Marshall, L. G. (1974). Late Pleistocene mammals from the 'Keilor Cranium Site', southwestern Victoria, Australia. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria 13: 63-85.

Matthews, Roger L., Fusco, Diana A., Gully, Grant A., Arnold, Lee, J., Demuro, Martina, Spooner, Nigel A., Wells, Roderick T. and Prideaux, Gavin J. (2025). Kiana Cliff: a new fossil vertebrate site of probable last interglacial age from Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. https://doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2025.2452015

McCoy, F. (1861). Untitled. The Argus (Melbourne) (October 1st) 4783: 5 (cols. 1-2).

McCoy, F. (1865). On the Bones of a New Gigantic Marsupial. Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 6: 25. [description of D. longiceps, a replacement name for D. annextans which he had previously described]

McCoy, F. (1869). On the fossil eye and teeth of the Ichthyosaurus australis (M’Coy), from the Cretaceous formations of the source of the Flinder’s River; and on the palate of Diprotodon, from the Tertiary limestone of Limeburner’s Point, near Geelong. In Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria (Vol. 2, pp. 77-78).

McCoy, F. (1876). Prodromus of the Palaeontology of Victoria. Decade 4. Melbourne.

McNamara, G. C. (1990). The Wyandotte Local Fauna: A new, dated, Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum (Proceedings of the De Vis symposium) 28(1): 285-297.

McNamara, Ken and Murray, Peter. (2010). Prehistoric Mammals of Western Australia. Welshpool, WA: Western Australian Museum. 107 pp.

Merrilees, Duncan. (1968). Man the destroyer: late Quaternary changes in the Australian marsupial fauna (Presidential Address, 1967). Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 51: 1-24.

Merrilees, Duncan. (1973). Fossiliferous deposits at Lake Tandou, New South Wales, Australia. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria 34: 177-182.

Michell, John and Rickard, Robert J. M. (1982). Living Wonders: Mysteries and Curiosities of the Animal World. London: Thames and Hudson. [p. 66-67]

Mitchell, Thomas L. (1838). Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia, with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix, and of the present colony of New South Wales. Vol. 1. London: T. & W. Boone, 343 pp.

Molnar, R.E. and Kurz, C. (1997). The distribution of Pleistocene vertebrates on the eastern Darling Downs, based on the Queensland Museum collections. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 117: 107-134. [record from Armour Station, Queensland]

Murray, P. F. (1984). Extinctions Downunder: a bestiary of extinct Australian late Pleistocene monotremes and marsupials. In: Martin, P. S. and Klein, R. G. (eds.). Quaternary Extinctions, a Prehistoric Revolution. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

Murray, P. F. (1991). The Pleistocene megafauna of Australia, pp. 1071-1164. In: Vickers-Rich, P., Monaghan, J. M., Baird, R. F., and Rich, T. H. Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australiasia. Pioneer Design Studio.

Murray, P., Megirian, D., Rich, T. H., Plane, M., Black, K., Archer, M., Hand, S. and Vickers-Rich, P. (2000). Morphology, systematics and evolution of the marsupial genus Neohelos Stirton (Diprotodontidae, zygomaturinae). Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory Research Report 6(6): 1-141.

Nguyen, J., & White, A. (2015). Digging up a Diprotodon in central NSW. Science Education News, 64(4), 26.

Owen, Richard. (1838b). On the osteology of the Marsupialia. Proc. Zoo. Soc. Lond. 6: 120-147. [Abstract]

Owen, Richard. (1843a). On the discovery of the remains of a mastodontoid pachyderm in Australia. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 11: 7-12.

Owen, Richard. (1843b). Additional evidence proving the Australian Pachyderm described in a former number of the ‘Annals’ to be a Dinotherium with remarks on the nature and affinities of that genus. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History 71: 329-332.

Owen, Richard. (1844). Description of a fossil molar tooth of a Mastodon discovered by Count Strzlecki in Australia. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 14: 268-271.

Owen, Richard. (1846). Description of a fossil molar tooth of a Mastodon: Discovered by Count Strzlecki in Australia. The Tasmanian journal of natural science, agriculture, statistics, &c. 2(11): 451-455. [pages: 451-452, 453-455]

Owen, Richard. (1870a). On the fossil mammals of Australia-Part III. Diprotodon australis, Owen. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London 160: 519-578, pis 35-50. [N. S. Pledge: "Reprinted (1877) in 'Researches on the fossil remains of the extinct mammals of Australia with a notice of the extinct marsupials of England"]

Owen, Richard. (1870b). Restoration of an Extinct Elephantine Marsupial (Diprotodon Australis). Royal Soc. of London.

Owen, Richard. (1877). Researches of the Fossil Remains of the Extinct Mammals of Australia; with a notice of the Extinct Mammals of England. London: J. Erxleben.

Owen, R. S. 1894. The life of Richard Owen by his grandson; with the scientific portions revised by C. Davies Sherborn. (Murray: London).

Pilling, A. R., & Waterman, R. A. (1970). Diprotodon to detribalization: studies of change among Australian aborigines. Michigan State Univ Pr. [relevant citation?]

Piper, Katarzyna J., Fitzgerald, Erich M. G. and Rich, Thomas H. (2006). Mesozoic to early Quaternary mammal faunas of Victoria, south-east Australia. Palaeontology 49(6): 1237-1262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00595.x

Playford, P. (n.d.). Geology of Windjana Gorge, Geikie Gorge and Tunnel Creek National Parks. Issued by the Department of Conservation and Land Management, Corno, Western Australia.

Pledge, Neville S. (1990). The Upper Fossil Fauna of the Henschke Fossil Cave, Naracoorte, South Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum (Proceedings of the De Vis Symposium) 28(1): 247-262.

Pledge, N. S. (1993). A century of Callabonna research. Conference on Australasian Vertebrate Evolution, Palaeontology and Systematics. Abstract, April 19-21, Adelaide, 1993.

Pledge, N. S. (1994). Recent Diprotodon discoveries in South Australia. Abstracts of the fourth conference on Australian vertebrate evolution, palaeontology and systematics, Adelaide, 19-21 April, 1993. Records of the South Australian Museum 1994. [Abstract]

Pledge, N. S., Prescott, J. R. and Hutton, J. T. (2002). A late Pleistocene occurrence of Diprotodon at Hallett Cove, South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 126(1): 39-44.

Price, Gilbert J. (2008). Taxonomy and palaeobiology of the largest-ever marsupial, Diprotodon Owen, 1838 (Diprotodontidae, Marsupialia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 153(2): 389-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00387.x

Price, Gilbert J., Fitzsimmons, Kathryn E., Nguyen, Ai Duc et al. (2021). New ages of the world's largest-ever marsupial: Diprotodon optatum from Pleistocene Australia. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2021.06.013 [Abstract]

Gilbert J. Price, Kyle J. Ferguson, Gregory E. Webb, Yue-xing Feng, Pennilyn Higgins, Ai Duc Nguyen, Jian-xin Zhao, Renaud Joannes-Boyau and Julien Louys. (2017). Seasonal migration of marsupial megafauna in Pleistocene Sahul (Australia–New Guinea). Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 284(1863): [pagination?]. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0785 [Abstract]

Price, Gilbert J. and Piper, Katarzyna J. (2009). Gigantism of the Australian Diprotodon Owen 1838 (Marsupialia, Diprotodontoidea) through the Pleistocene. Journal of Quaternary Science 24(8): 1029-1038.

Price, Gilbert J. and Sobbe, I. H. (2005). Pleistocene palaeoecology and environmental change on the Darling Downs, southeastern Queensland, Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 51(1): 171-201. [subfossil remains from Darling Downs, Queensland]

Price, Gilbert J. and Sobbe, Ian H. (2011). Morphological variation within an individual Pleistocene Diprotodon optatum Owen, 1838 (Diprotodontinae; Marsupialia): implications for taxonomy within diprotodontoids. Alcheringa 35(1): 21-29.

Prideaux, Gavin J. (2004). Systematics and evolution of the sthenurine kangaroos. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 146: i-xviii, 1-623.

Pritchard, G. B. (1899). On the occurrence of Diprotodon australis (Owen) near Melbourne. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 12(1): 112-114.

Quirk, Susan and Archer, Michael (eds.), with Schouten, Peter (illustrator). (1983). Prehistoric animals of Australia. Sydney: Australian Museum. 80 pp.

Reed, Elizabeth H. and Bourne, Steven J. (2000). Pleistocene fossil vertebrate sites of the south east region of South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 124(2): 61-90. [D. optatum and D. australis]

Reed, Elizabeth H. and Bourne, Steven J. (2009). Pleistocene Fossil Vertebrate Sites of the South East Region of South Australia II. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 133(1): 30-40.

Rich, Thomas H. V. (1983). The largest marsupial Diprotodon optatum. Pp. 62–63 in Quirk, S. and Archer, M. (eds) Prehistoric animals of Australia. Sydney: Australian Museum.

Rich, Thomas H. V. (1984). Australia's largest marsupial, Diprotodon: its ancestry, palaeobiology and extinction. Pp. 995–97 in Archer, M. and Clayton, G. (eds) Vertebrate zoogeography and evolution in Australasia (Animals in space and time). Carlisle, Western Australia: Hesperian Press.

Rich, Thomas H. (1985a). Megalania prisca Owen, 1859: The Giant Goanna, pp. 152-155. In: Vickers-Rich, Patricia and van Tets, Gerard Frederick. (eds.). Kadimakara: Extinct Vertebrates of Australia. Lilydale, Victoria: Pioneer Design Studio. 284 pp.

Rich, Thomas H. (1985b). Diprotodon Owen, 1838: Diprotodon, pp. 240-244. In: Vickers-Rich, Patricia and van Tets, Gerard Frederick. (eds.). Kadimakara: Extinct Vertebrates of Australia. Lilydale, Victoria: Pioneer Design Studio. 284 pp.

Rich. T. H. V. (1991). Monotremes, Placentals and Marsupials: Their Record in Australia and its Biases. In: Vickers-Rich, P., Monaghan, J. M., Baird, R. F., and Rich, T. H. Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australiasia. Pioneer Design Studio.

Roberts, Richard G, Flannery, Timothy F., Ayliffe, Linda, Yoshida, Hiroyuki, Olley, Jon M., Prideaux, Gavin J., Laslett, Geoff M., Baynes, Alexander, Smith, M. A., Jones, Rhys I. and Smith, Barton L. (2001). New ages for the last Australian megafauna: Continent-wide extinction about 46,000 years ago. Science 292(5523): 1888-1892. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1060264

Ruhen, O. (1976). The day of the Diprotodon. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton, 32 pp. [According to J. H. Calaby: "Juvenilia; An imaginative fictional account of the extinction of the Diprotodon at Lake Callabonna. A highly unlikely tale"]

Runnegar, B. (1983). A Diprotodon ulna chewed by the marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex. Alcheringa 7: 23-25.

Saltré, Frédérik et al. (In Press, 2015). Uncertainties in dating constrain model choice for inferring extinction time from fossil records. Quaternary Science Reviews. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2015.01.022 [Abstract]

Schultz, L. D. (2004). The Tedford and Wells fossil collection: a faunal analysis of the Plio-Pleistocene stratigraphic formations of the Lake Eyre Basin. Unpublished B.Sc. (Hons) thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide.

Scott, H. H. (1910). The Tasmanian Diprotodon. Examiner (Launceston), Tuesday, 23 August, p. 7.

Scott, H. H. and Lord, C. E. (1920a). Studies in Tasmanian mammals, living and extinct. Number I. Nototherium mitchelli (a marsupial rhinoceros). Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 1920: 13-15.

Scott, H. H. and Lord, C. E. (1920b). Studies in Tasmanian mammals, living and extinct. Number II. Section 1: The history of the genus Nototherium. Section 2: The osteology of the cervical vertebrae of Nototherium mitchelli. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 1920: 17-32.

Sharp, Alana Clare. (2014). Three dimensional digital reconstruction of the jaw adductor musculature of the extinct marsupial giant Diprotodon optatum. PeerJ 2: e514.

Sharp, Alana Clare. (2015). Cranial form and function of the largest ever marsupial, Diprotodon optatum Owen, 1838 (Marsupialia: Diprotodontinae). Doctorate thesis, Monash University. [Abstract]

Sharp, Alana Clare and Rich, T. H. (2016). Cranial biomechanics, bite force and function of the endocranial sinuses in Diprotodon optatum, the largest known marsupial. Journal of Anatomy. doi: 10.1111/joa.12456 [Abstract]

Smith F.A., Lyons S.K., Ernest S.K.M., Jones K.E., Kaufman D.M., Dayan T., Marquet P.A., Brown J.H., Haskell J.P. 2003 Body mass of late Quaternary mammals. Ecology 84(12), 3403-3403.

Stephenson, N. G. (1963). Growth gradients among fossil monotremes and marsupials. Palaeontology 6(4): 615-624.

Stirling, E. C. (1893). [Extract from a letter concerning the discovery of Diprotodon and other mammalian remains in South Australia]. Proceedings of the Zoological Society, London 1893: 473-475.

Stirling, E. C. (1901). [Diprotodon australis.) Museum Journal. (London) 1: 114-115 (1901-1902)

Stirling, E. C. (1907). Reconstruction of Diprotodon from the Callabonna deposits, South Australia. Nature (London) 76: 543-544, figs. 1, 2.

Stirling, E. C. and Zietz, A. H. C. (1899). Fossil remains of Lake Callabonna. Part I. Description of the manus and pes of Diprotodon australis, Owen. Memoirs of the Royal Society of South Australia 1: 1-40, pis. I-XVIII. Abstr., Nature (London) 61: 275-278, 2 figs. (1900). [First page]

Tedford, Richard H. (1973). The Diprotodons of Lake Callabonna. Australian Natural History 17(11): 349-354.

Tedford, Richard H. (1994). Lake Callabonna: 'Veritable necropolis of gigantic extinct marsupials and birds'. Abstracts of the fourth conference on Australian vertebrate evolution, palaeontology and systematics, Adelaide, 19-21 April, 1993. Records of the South Australian Museum 1994. [Abstract] [curiously: "possibly a second, smaller species [of Diprotodon]"]

Tedford, R. H., and R. T. Wells. (1990). Pleistocene deposits and fossil vertebrates from the Dead Heart of Australia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 28: 263-284.

Tedford, R.H., Wells, R.T., and Barghoorn, S.F. (1992). Tirari Formation and contained faunas, Pliocene of the Lake Eyre Basin, South Australia. The Beagle, Records of the Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences 9: 173-194.

Tindale, N. B., Fenner, F. J. and Hall, F. J. (1935). Mammal bone beds of probable Pleistocene age, Rocky River, Kangaroo Island. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 59: 103-106.

Travouillon, Kenny J., Jackson, Stephen, Beck, Robin M. D., Louys, Julien, Cramb, Jonathan, Gillespie, Anna, Black, Karen, Hand, Suzanne, Archer, Michael, Kear, Benjamin, Hocknull, Scott, Phillips, Matthew, McDowell, Matthew, Fitzgerald, Erich M. G., Brewer, Phillipa and Price, Gilbert J. (2023). Checklist of the Fossil Mammal Species of Australia and New Guinea. Available from: https://www.australasianpalaeontologists.com/national-fossil-species-lists [Accessed 2 March 2025]

Travouillon, Kenny J., Jackson, Stephen, Beck, Robin M. D., Louys, Julien, Cramb, Jonathan, Gillespie, Anna, Black, Karen, Hand, Suzanne, Archer, Michael, Kear, Benjamin, Hocknull, Scott, Phillips, Matthew, McDowell, Matthew, Fitzgerald, Erich M. G., Brewer, Phillipa and Price, Gilbert J. (2024). Checklist of the Fossil Mammal Species of Australia and New Guinea. Available from: https://www.australasianpalaeontologists.com/national-fossil-species-lists [Accessed 24 November 2024]

Travouillon, Kenny J., Jackson, Stephen, Beck, Robin M. D., Louys, Julien, Cramb, Jonathan, Gillespie, Anna, Black, Karen, Hand, Suzanne, Archer, Michael, Kear, Benjamin, Hocknull, Scott, Phillips, Matthew, McDowell, Matthew, Fitzgerald, Erich M. G., Brewer, Phillipa and Price, Gilbert J. (2025). Checklist of the Fossil Mammal Species of Australia and New Guinea. Available from: https://www.australasianpalaeontologists.com/national-fossil-species-lists [Accessed 1 March 2025]

Trezise, P. (1993). Dream road: A journey of discovery. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. ["[proposes] that an image from Cape York Peninsula is of Diprotodon"*]

Trueman, Clive N. G., Field, Judith H., Dortch, Joe, Charles, Bethan and Wroe, Stephen. (2005). Prolonged coexistence of humans and megafaunain Pleistocene Australia. PNAS 102(23): 8381-8385. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408975102

Tunbridge, Dorothy. (1988). Flinders Ranges Dreaming. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Tunbridge, Dorothy. (1991). The Story of the Flinders Ranges Mammals. Kenthurst: Kangaroo Press. 96 pp. [p. 72]

Turnbull, William D; Lundelius, Ernest L and Tedford, Richard H. (1992). A Pleistocene marsupial fauna from Limeburner's Point, Victoria, Australia. The Beagle: Records of the Museums and Art Galleries of the Northern Territory 9: 143-171. [Abstract]

Tyndale-Biscoe, H. (2005). Life of Marsupials. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing.

Van Huet, S. et al. (1998). Age of the Lancefield megafauna: a reappraisal. Australian Archaeology 46: 5-11.

Van Huet, Sanja. (1999). The taphonomy of the Lancefield swamp megafaunal accumulation, Lancefield, Victoria. In: Baynes, Alexander and Long, John A. (eds.). Papers in vertebrate palaeontology. Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement 57: 331-340.

Vanderwal, Ron and Fullagar, Richard. (1989). Engraved Diprotodon tooth from the Spring Creek locality, Victoria. Archaeology in Oceania 24(1): 13-16. [Abstract]

Vickers-Rich, P., T. H. Rich, L. S. Rich and T. Rich. (1997). Diprotodon and Its Relatives. The Little Prehistory Books. Sydney: Kangaroo Press. 25 pp.

Waterhouse, George Robert. (1845). A Natural History of the Mammalia. Volume 1, Containing the Order Marsupiata or Pouched Animals. London: Hippolyte Baillière. 553 pp + 20 pls.

Waters, B. T. (1969). Osteology of Diprotodon. University of California.

Webb, Steve. (2008). Megafauna demography and late Quaternary climatic change in Australia: A predisposition to extinction. Boreas 37: 329-345.

Webb, Steve. (2009). Late Quaternary distribution and biogeography of the southern Lake Eyre basin (SLEB) megafauna, South Australia. Boreas 38: 25-38.

Wellington, Susan and Milne, Nick. (1999). The functional morphology of the marsupial hind limb in the Diprotodontidae and some extant species. Abstracts from the 6th CAVEPS, Perth, 7-11 July, 1997. In: Baynes, Alexander and Long, John A. (eds.). Papers in vertebrate palaeontology. Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement 57: 422.

Wells, R. T., R. Grün, J. Sullivan, M. S. Forbes, S. N. Dalgairns, E. A. Bestland, E. J. Rhodes, K. E.Walshe, N. A. Spooner, and S. Eggins. (2006). Late Pleistocene megafauna site at Black Creek Swamp, Flinders Chase National Park, Kangaroo Island, South Australia. Alcheringa Special Issue 1: 367-387.

Wells, R. T., and R. H. Tedford. (1995). Sthenurus (Macropodidae: Marsupialia) from the Pleistocene of Lake Callabonna, South Australia. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 225: 1-111.

White, J. Peter and Flannery, Tim. (1995). Late Pleistocene fauna at Spring Creek, Victoria: A re-evaluation. Australian Archaeology 40: 13-17. [link to pdf copy at bottom of the page]

Williams, Dominic L. G. (1980). Catalogue of Pleistocene vertebrate fossils and sites in South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 104(5): 101-115.

Williams, Dominic L. G. (1982). Late Pleistocene Vertebrates and Palaeo-environments of the Flinders and Mount Lofty Ranges. Unpublished Ph.D thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide.

Willis, P. M. A. and Molnar, Ralph E. (1997). Identification of large reptilian teeth from Plio–Pleistocene deposits of Australia. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 130(3-4): 79-92.

Woodward, Arthur Smith. (1907). I.—On a Reconstructed Skeleton of Diprotodon in the British Museum (Natural History). Geological Magazine - GEOL MAG 4(8): [pagination?].

Woodward, H. P. (1890). Annual General Report for 1888-1889. Geological Survey of Western Australia. Perth: Government Printer.

Wroe, Stephen; Crowther, Mathew; Dortch, Joe, and Chong, John. (2004). The size of the largest marsupial and why it matters. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271: S34-S36.

Zietz, A. H. C. (1890a). Diprotodon remains. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 13: 236.

Zietz, A. H. C. (1890b). (Abstract of Proceedings). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia 13: 245. [relevant citation?]

http://museum.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/VOL.1%20PART%201%201910%20P509.941%20REC.pdf

*This quote is taken from: Bednarik, Robert G. (2013). Myths About Rock Art. Journal of Literature and Art Studies 3(8): 482-500.

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-11-24/teeth-of--rhinoceros-sized-wombat-found-at-lancefield-swamp/8053196

https://twilightbeasts.wordpress.com/2016/10/12/squishy-bear-face/

https://twilightbeasts.wordpress.com/2014/10/06/an-adorable-goofy-looking-giant/

https://www.australianmuseum.net.au/blogpost/museullaneous/meet-darren-the-diprotodon

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/84659#page/253/mode/1up

http://extinctanimals.proboards.com/thread/16034/diprotodon-optatum

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-06-28/giant-wombat-monaro-fossil-museum/11258792